From Migration to Reintegration: Examining the Post-Return Experiences of Georgian Women

Downloads

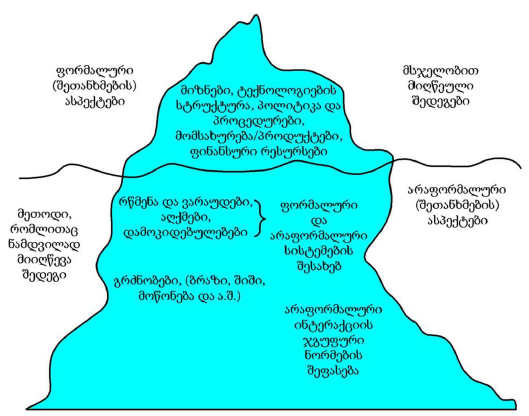

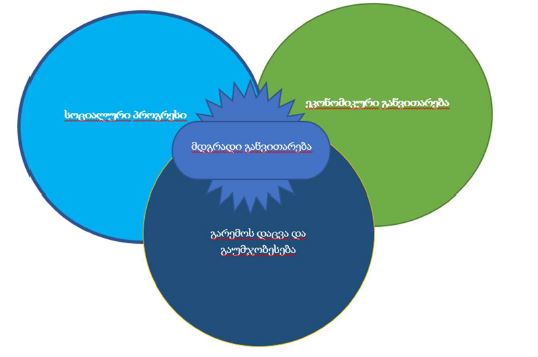

Over the past three decades, there has been a significant rise in female migration globally, a trend also evident in Georgia. The 2014 general population census in Georgia revealed a higher number of female migrants compared to male migrants, with many women engaging in care work in countries such as Greece, Turkey, and Italy. This study aims to examine the challenges that returned women migrants face in Georgian society, focusing on their reintegration at the micro (family), mezzo (community), and macro (labour market) levels. Utilising a qualitative research approach, the study involved in-depth interviews with seven returned women migrants and five daughters of migrant mothers who remained in migration. Additionally, ethnographic analysis of Facebook posts and comments provided further insights into the reintegration experiences of ex-migrants. The research sought to understand the factors that facilitate or hinder the reintegration process, including the impact of separation periods and family members' experiences during migration and the reasons for returning from migration. The findings indicate that reintegration is a complex process influenced by various factors. On the labour market level, returned migrants face significant challenges due to their age, deskilling, and the new labour market dynamics that emerged during their absence. Due to unfamiliarity and limited resources, many prefer to continue working in care roles, which they performed abroad. On the community level, cultural and behavioural differences between the host and home countries complicate resocialisation. Social inequality and a perceived decline in service standards also hinder reintegration. Long-term migration has significantly altered family dynamics at the family level, making it difficult for returnees to readjust. Increased irritability and feelings of exclusion are common among returnees, who struggle to reintegrate into family roles and responsibilities. Families' financial dependence on remittances further complicates the reintegration process. Despite these challenges, continuous communication with family members and the support of relatives can facilitate reintegration. From a functionalist perspective, the reintegration challenges are seen as disruptions to the social equilibrium, where returning migrants struggle to reclaim their former roles and functions within the societal system.

Downloads

Antman, F. M. (2012). The impact of migration on family left behind. In International Handbook on the Economics of Migration (pp. 293–308). Elgar Original. https://docs.iza.org/dp6374.pdf

Arowolo, O. O. (2002). Return migration and the problem of reintegration. International Migration, 38(5), 59-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00128

Azose, J. J., & Raftery, A. E. (2019). Estimates of emigration, return migration, and transit migration between all pairs of countries. PNAS, 116(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1722334116

Cassarino, J. P. (2004). Theorising return migration: The conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 6(2), 253-279. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1730637

Castañeda, E. (2012). Living in limbo: Transnational households, remittances and development. International Migration, 51(S1), e13-35.

Chammartin, G. M. F. (2002). The feminization of international migration. International Migration Programme: International Labour Organization.

Durkheim, É. (1984). The division of labour in society. (W. D. Halls, Trans.). Free Press. (Original work published 1893)

Guruge, S., Kanthasamy, P., Jokarasa, J., Chinichian, M., Paterson, P., Wai Wan, T. Y., Shirpak, K. R., & Sathananthan, S. (2010). Older women speak about abuse & neglect in the post-migration context. Women's Health and Urban Life, 9(2), 15-41. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/25498

International Organization for Migration. (2019). An integrated approach of reintegration. https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/documents/atip_levant/iom-reintegrationhandbook-module_1-an-iintegrated-approach-to-reintegration.pdf

IOM UN Migration. (2024). World Migration Report. International Organization for Migration. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2024

King, R., & Lulle, A. (2022). Gendering return. In R. King & K. Kuschminder (Eds.), Handbook of Return Migration. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage Publications.

Krelinova, K., & Ormotsadze, N. (2021). National study of reintegration outcomes among returned migrants in Georgia. IOM Georgia. https://georgia.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1311/files/iom_reintegration-outcomes-georgia-study-june-2021.pdf

Lee, E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1), 47-57. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0070-3370%281966%293%3A1%3C47%3AATOM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B

Little, W. (2013). Introduction to sociology – 1st Canadian edition. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/

Mataradze, T. (2019 (2015)). Rural locals, distant states: Citizenship in contemporary rural Georgia. [Doctoral thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg]. https://doi.org/10.25673/13996

Mataradze, T., & Mühlfried, F. (2009). Leaving and being left behind: Labor migration in Georgia. Caucasus Analytical Digest, (4). https://laender-analysen.de/cad/pdf/CaucasusAnalyticalDigest04.pdf

Merton, R. K. (1957). Social theory and social structure. Free Press.

OECD iLibrary. (2020). Number of Georgian emigrants and their socio-demographic characteristics. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/c282e9fe-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/c282e9fe-en

Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. Free Press.

Sahadeo, J. (2007). Druzhba Narodov or second-class citizenship? Soviet Asian migrants in a post-colonial world. Central Asian Survey, 26(4), 559-579.

Simmel, G. (1908). The stranger. In K. H. Wolff (Ed. & Trans.), The sociology of Georg Simmel (pp. 402-408). Free Press.

Suny, R. G. (1996). On the road to independence: Cultural cohesion and ethnic revival in a multinational society. In R. G. Suny (Ed.), Transcaucasia, nationalism, and social change: Essays in the history of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia (pp. 377-400). University of Michigan Press.

Sztompka, P., Alexander, J. C., Eyerman, R., Giesen, B., & Smelser, N. J. (2004). Cultural trauma and collective identity. University of California Press.

Caritas Internationalis (2010, February 17). The Female Face of Migration. https://www.caritas.org/includes/pdf/advocacy/FFMCaritasPolicyDoc.pdf

Vanore, M. T. (2015). Family-member migration and the psychosocial health outcomes of children in Moldova and Georgia [Doctoral dissertation]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Family-member-migration-and-the-psychosocial-health-Vanore-Vanore/27fd2ac6325363c6bfb2d975dbaefde8443e73cb

Zurabishvili, T., & Zurabishvili, T. (2010). The feminization of labor migration from Georgia: The case of Tianeti. Laboratorium, 1(1). http://www.soclabo.org/index.php/laboratorium/article/view/170/334

ბარქაია, მ. (2016, December 15). რადიკალური დასვენების აჩრდილი: დროის კოლონიზაციის კავშირი დასაქმებულთა ექსპლუატაციასა და ქალთა ჩაგვრასთან. ჰაინრიჰ ბიოლის ფონდი. https://feminism-boell.org/ka/2016/12/15/radikaluri-dasvenebis-achrdili-drois-kolonizaciis-kavshiri-dasakmebulta-ekspluataciasa-da

გოგსაძე, გ. (2018). მოსახლეობის გეოგრაფია (სახელმძღვანელო) (2nd ed.).

კალაძე, ს., & დავითულიანი, ლ. (2018). საბერძნეთიდან დაბრუნებული ემიგრანტი ქალების რეინტეგრაცია ქართულ შრომის ბაზარზე. სტუდენტთა ჟურნალი სოციალურ მეცნიერებებში. https://sjss.tsu.ge/img/emigranti-qalebi%201.pdf

მიგრაციის საერთაშორისო ორგანიზაცია. (2024). საქართველოში დაბრუნება. IOM Georgia. https://georgia.iom.int/ka/node/113176

საქართველოს სტატისტიკის ეროვნული სამსახური. (2014). ემიგრანტების განაწილება ასაკისა და სქესის მიხედვით. https://www.geostat.ge/ka/modules/categories/743/gare-migratsia

საქართველოს სტატისტიკის ეროვნული სამსახური. (2023). იმიგრანტებისა და ემიგრანტების რიცხოვნობა სქესისა და მოქამაქეობის მიხედვით. საქართველოს სტატისტიკის ეროვნული სამსახური. https://www.geostat.ge/ka/modules/categories/322/migratsia

ჩაჩავა, მ. (2020). საქართველოში დაბრუნებული ემიგრანტი ქალების ანაზღაურებადი და აუნაზღაურებელი შრომა. ჰაინრიჰ ბიოლის ფონდი. https://feminism-boell.org/ka/2020/12/03/sakartveloshi-dabrunebuli-emigranti-kalebis-anazghaurebadi-da-aunazghaurebeli-shroma

ჩაჩავა, მ., & ზუბაშვილი, ნ. (2023). ქართველი შრომითი მიგრანტი ქალების სოციალურ-ეკონომიკური სტაბილურობა. ქალები საერთო მომავლისთვის (WECF) - საქართველო. https://www.undp.org/ka/georgia/publications/georgian-migrant-women-study

Copyright (c) 2024 Georgian Scientists

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.